Running in Place (with Distinction)

A Theory of the Leisure Class in Modern India (Part 2)

“The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters.”

- Antonio Gramsci

ICYMI: This is part 2 of a series adapting Veblen’s Theory of the Leisure Class to India. Go here to catch up on the historical development of the leisure class in India from the age-old caste hierarchy to the influence of the British Raj, and the post-independence economic miracle beginning in the late 80s.

Turning our attention from the historical antecedents to the actually-existing leisure class in present-day India, we can identify several domains where Veblen’s theories manifest themselves. I’ll focus my attention on three of these:

The relationship between work and marriage

Education, and

The enduring caste-based stratification of occupations

Each case illustrates the interplay of conspicuous display, emulative behaviour, and status preservation in the here and now.

Leisure Beyond Leisure: Status, Work, and Women

As a liberal, Western-educated democracy with a vibrant electoral marketplace, India has always been expected to live up to that billing. From its adoption in 1950, the Constitution of Independent India has guaranteed universal adult franchise to all citizens irrespective of gender, caste, income, or education level. To most political theorists until fairly recently, this was cause enough to expect that given enough time, India’s low female labour participation would improve. If not to total parity like in the Communist states, then at least to the degree in the more enlightened Western European nations. Women’s franchise was supposed to lead to emancipation in a sort of happy slippery slope (a water slide?)

Reality has been a mixed bag. The status of women in society has improved in real terms: foeticide, infanticide, child marriage, maternal mortality, and most other markers of population health are improving at an impressive clip. Even with education, women are catching up to men: a girl born in the 2020s can be expected to receive ~6 more years of schooling than a girl born around independence. And while in school, her scores can be expected to be ahead of the average boy of the same age - a trend seen across most modern societies.

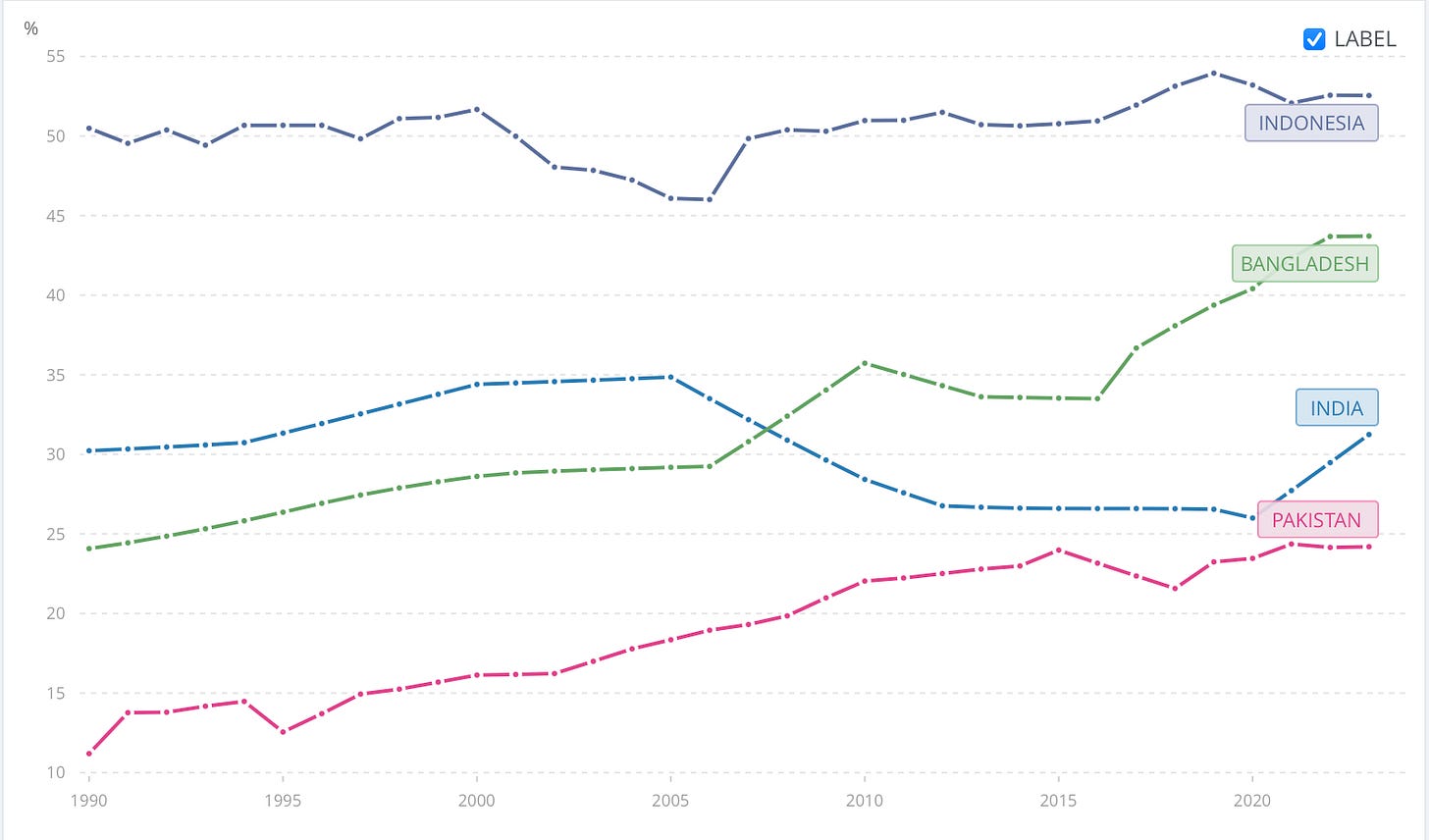

Yet, one of the most troubling (and hotly-debated) statistics about modern India is its extraordinarily low female labour force participation rate. As of the early 2020s, only about 25-30% of Indian women are in the workforce, compared to ~60% in China, 40% in Bangladesh, and ~25% in conservative Pakistan. Even more grim is the fact that this ratio appears to be falling over time - from around 50% around independence to just over half that now.

This can seem puzzling because India has seen rising education levels for women, declining fertility rates, and economic growth – all factors that usually lead to more women working. Part of the explanation, beyond issues of job availability and safety — that Alice Evans lays out quite neatly on her Substack — lies in cultural expectations tied to status. In many communities, when a household’s income rises or when a woman attains a certain social status (through marriage or caste), the expectation is that she will withdraw from work. Employment for women is often not just an economic choice but a social signal: a working wife or daughter might imply the family needs her income, whereas a woman who stays at home indicates the family’s financial comfort and honour. This dynamic is especially prevalent among upwardly mobile urban families and upper-caste groups.

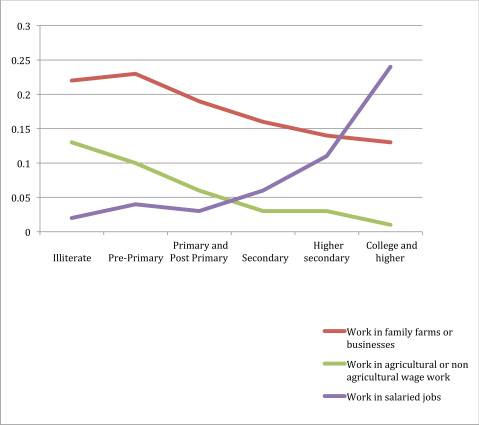

Indeed, data shows an inverted U-shape of women’s employment in India – women from the poorest families work out of necessity (often in menial jobs), those from slightly better-off families drop out of work to become full-time homemakers, and only some of the highly educated women in top urban echelons re-enter professional work. The “income effect” is such that the moment a family can afford to live on the male breadwinner’s salary, the woman is pulled back into the home.

To quote the researchers:

“[…] educated women look mainly for better quality jobs, especially salaried work. The inference might be that if all or most available jobs were salaried, Indian women would show the usual positive relationship of higher rates of employment with more education. However, such jobs are limited and are accessible mainly with higher levels of education. If appropriate jobs were available for women with intermediate levels of education, we might expect higher levels of their labor force participation.”

In essence, even beyond high rank, the aspiration of many families is to reach a stage where their women can devote themselves to domestic leisure or at most “genteel” pursuits (like hobby classes, kitty parties, or supervising servants). Henrike Donner, in research on Indian middle classes, noted that middle-class women often use motherhood and home-making to differentiate themselves from both the poor and the very rich – it’s a “much coveted privilege” to be able to choose a C-section or stay home with the child, choices that are made possible by — and therefore signal — one’s class position.

The flip side is that this norm reinforces patriarchy and economic dependence of women, leading to phenomena like the dualistic archetype of doting son and educated unemployed housewife. It’s not uncommon to meet an Indian woman with a college degree (even one from a prestigious college) who isn’t working for pay because her family or in-laws prefer she focus on the home. The family gains status by saying, “Our daughter-in-law is an MBA, but we don’t let her work – we take good care of her.” In essence, her education itself becomes a status ornament (much as Veblen noted that education can be pursued as a mark of refinement), but her non-use of that education in the job market becomes a mark of the family’s wealth. This has serious economic implications for the long-term health of the Indian economy but socially it persists because it adheres to a Veblenian logic of reputability through leisure.

Of course, these patterns are not monolithic: many women in India do work and are challenging norms, especially in big metros and among the younger generation that has grown up with a certain expectation of an urban life with consumer electronics and branded icons of luxury. Female professionals in IT companies, startups, and government roles are more visible now than before, and attitudes are slowly shifting. Yet, the overall statistics and cultural undercurrents suggest that the leisured woman as a status symbol is still very much a part of Indian society.

Until working women are seen as equally “respectable” as non-working women across social classes, this aspect of Veblen’s theory will hold true in India. While most Western societies have had to wrestle with the status of household work as unpaid labour that needs to be recognised in other non-monetary terms, the Indian perspective holds that she is performing vicarious leisure on behalf of the family, her very withdrawal from the workforce broadcast as proof of her family’s elevated status.

Arranged Marriages and the Business of Status Reproduction

Related to the issue of women’s non-participation in labour is the continued persistence of arranged marriages. Marriage in India is not just a personal union; it is a family institution deeply tied to status, caste, and class. Over 80% of Indian marriages are arranged in some form by the families (including many among urban educated classes). This system has long been a mechanism for preserving or improving social status through a logic of mutually-beneficial exchange. Veblen has a term for this: “pecuniary transactions”, though in this case the transaction involves social capital and secretive dowries rather than open market prices.

Veblen wrote about women as trophies and marriage as a form of ownership transfer in archaic societies. In modern India, the arranged marriage custom often treats the bride and groom as bearers of family status to be matched and exchanged. “Marriage becomes one of the main institutions to ensure the reproduction of class,” observes Donner, explaining why despite modernisation, arranged matches remain the norm. Families meticulously negotiate matches where caste, family wealth, education, and even skin complexion are evaluated to strike the “right” balance.

An ideal match generally maintains or elevates the family’s social standing – daughters are married “up” (hypergamy) to grooms with equal or better economic prospects, while sons are married to brides who bring dowry or social connections. This is changing slowly, but the underpinning mindset is alive: a successful marriage for many is one that enhances the family’s reputation.

The role of dowry in marriages exemplifies the commodification of status. Despite being illegal since 1961, dowry practice is widespread as a socially expected transfer from the bride’s family to the groom’s. It’s often rationalised in economic terms (e.g. helping set up the couple) but in practice has become a normal and expected part of the social transaction that is marriage. The groom’s education, job title, and income often determine the dowry “rate” – for example, an engineer in the US or a civil servant might command a hefty dowry, which is essentially a price on his status. Conversely, the bride’s family paying dowry hopes to gain the prestige of marrying their daughter into an ostensibly higher status household. This is pecuniary emulation through marriage: families use wealth (dowry) to buy into a higher status alliance, while those receiving dowry use it to signal their superior standing. Reports abound of marriage negotiations where the groom’s family explicitly demands cash, a car, or property – turning the marriage into a blatantly pecuniary deal. The tragedy is that these can lead to “dowry deaths” or domestic abuse if the dowry expectations aren’t met, a violent outcome of treating marriage as a status contest.

Beyond dowry, arranged marriage discussions on social platforms reveal how entrenched the status mindset is. The obsession with certain degrees in the marriage market is especially telling: anecdotally, being an IAS officer or an Ivy League graduate makes one a star on the marriage circuit, attracting dozens of proposals, whereas a less-educated but otherwise decent individual might be passed over. Thus, education (more precisely, elite education) and employment become conspicuous credentials in the marriage market – not entirely unlike how, in Veblen’s time, a gentleman’s club membership or lineage was a marriage credential.

The continuity with Veblen’s concept of women as status symbols is also evident. In many arranged marriages, the bride’s role (especially in affluent families) is implicitly to enhance the family’s status by her conduct and appearance. Families often prefer a daughter-in-law who is well-educated (for genes and grace) but also willing to be a homemaker – effectively, the modern equivalent of the trophy wife. A stark example is how “arranged marriage resumes” emphasise the woman’s qualifications and beauty, but it’s understood that she may not use those qualifications professionally after marriage. Marrying a beautiful, cultured woman who will not “need” to work is a double win for a status-conscious groom’s family – they acquire a vicarious leisure asset. On the other side, the bride’s family often assesses whether the groom can maintain her in comfort (will she have servants? a nice car? no joint family drudgery?). The ideals of the “Brahminical housewife” and the Victorian gentlewoman converge in modern Indian matrimonial expectations.

But it’s easy to overstate the case and despite everything, change is afoot. Love marriages (self-choice marriages) are slowly rising, and the stigma around them is lessening among urban youth. Same-sex marriages, while not legally recognised yet, have entered public conversation after decriminalization of homosexuality – potentially subverting the old marriage formulas. Furthermore, the skewed sex ratio and continued emigration has allowed many young women now to openly say they want a spouse who treats them as an equal, not as an owned object or a service-provider.

Still, this is not to imply that arranged-marriage couples are in any way inferior to love-marriage relationships or less capable of love, affection, or lifelong companionships filled with warmth, support and mutual encouragement. My only point is that anything that defies the “same-faith, arranged, heterosexual, lifelong union” norm has to be justified and is measured against this ideal. The idea of marriage has managed to incorporate advancements in technology to emerge a robust institution of pecuniary and reputational exchange: families trade brides and grooms the way firms trade assets, aiming to maximise their status returns. Until the balance between individual choice and family status tilts decisively in favour of individuals (which may take another generation or more), Indian marriages will remain a fascinating (if somewhat uneasy) theatre to watch Veblen’s ideas in action.

The Education Frenzy: Competitive Exams as Conspicuous Achievement

Few things capture the Indian middle class psyche as strongly as the pursuit of educational prestige. In Veblen’s time, acquiring education and scholarly degrees was already a way the leisure class could distinguish itself. The focus on classics and humanities meant that it was easy to view formal education as a “honorific” activity with no immediate economic use. In today’s India, the value placed on degrees and competitive exam success has reached a fever pitch, turning certain exams into holy grails of status – even when the odds of success are abysmally low. The most illustrative examples are the many iterations of the JEE (the artist formerly known as the “Indian Institute of Technology Joint Entrance Exam”) for engineering and the UPSC Civil Services Exam (which selects the IAS officers who we came across in part 1). These exams have spawned entire ecosystems of coaching institutes, mythologies of hardship, and social admiration for the “toppers.”

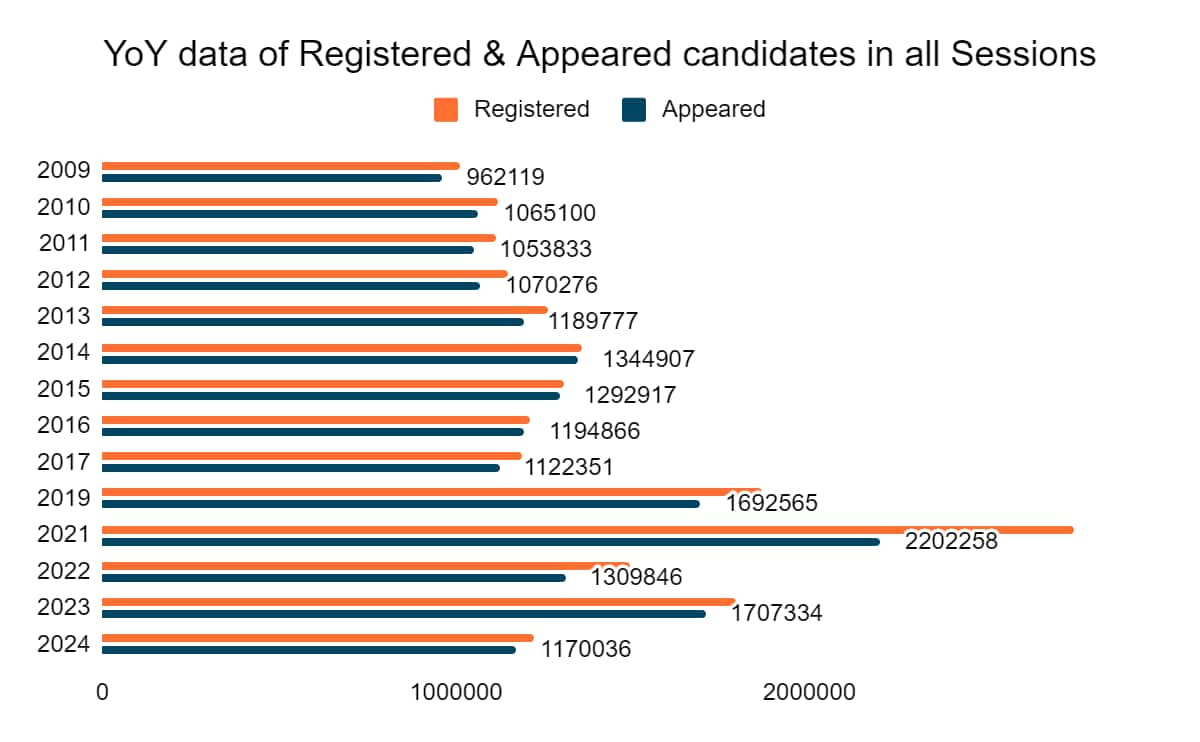

Consider the numbers: each year about 1.3 million students appear for the IIT entrance (JEE Main) for roughly 16,000 seats in the prestigious IITs. Similarly, the UPSC exam sees around 1 million aspirants chasing 700–1000 civil service positions, meaning only 0.1–0.2% will succeed. Despite such punishing odds – JEE has a success rate well under 1%, and UPSC about 0.2% – millions of families invest time, money, and emotional energy in this quest.

This phenomenon is best viewed as a sort of “pecuniary accomplishment”. Getting into an IIT or becoming an IAS officer is not just about the job or education itself; rather, it bestows a social cachet that is unparalleled. An IIT alumnus carries a halo in most social interactions and an IAS officer commands respect in any room. So even if 99% of aspirants fail, the collective fixation persists because those who win become part of the new leisure class elite, and everyone else basks vicariously in it or at least tries to copy it.

From a Veblenian view, one could say these competitive exams are a form of conspicuous waste of effort for many, and conspicuous leisure in the form of scholarship for the few who succeed. The lengths to which aspirants go — years in coaching factories like Kota, channeling the boundless energy of teenage years towards 16-hour study days — is a form of deferred leisure (or self-inflicted toil) in hopes of reaping lifetime honour.

Society, for its part, almost fetishizes this struggle: the media glorifies stories of poor kids who studied under streetlights to crack IIT, or the topper who gave up a corporate salary to join IAS. The process itself has become a status theatre. When results come out, successful candidates’ faces are splashed in newspapers, and coaching centres advertise their toppers like Olympic champions.

For the unsuccessful masses, there is often quiet despair or a stigma of failure – a human cost to this emulative pressure. In Kota, Rajasthan – infamous for cram schools – 23 students died by suicide in 2023 alone amid exam stress. This is a dark manifestation of the Veblenian competition for status: when the stakes of emulation are life-defining and the system is zero-sum, it can drive people to extreme distress. More sobering reading here.

What’s notable is how educational and exam success have become proxies for “leisure class” membership in a modern meritocratic guise. Unlike in Veblen’s era where birth and inherited wealth decided status, in India there is at least an ideal (if not entirely reality) that cracking these exams can elevate someone from any background to the elite. In recent years, top exam rankers from humble origins have indeed joined the ranks of IAS or IIT alumni - and many budding leaders have channelled their scholarly prowess into political success, which reinforces the aspirational appeal across classes. But once they ascend, they often adopt the lifestyle and consumption patterns of the traditional elite – thereby refreshing that class with new blood but old behaviours.

In many ways, the exam mania also reflects the scarcity of other avenues for upward mobility or recognition. In a society of over 1.4 billion, an IIT seat or IAS post is a distinguishing badge that cuts through the crowd. It’s a form of cultural capital that commands respect without needing further proof. That’s why even those who ultimately pursue other careers often prefix their bios with “IIT alumnus” or “UPSC rank X (former)” – the identity itself has capital. It’s telling that in matrimonial ads or dating profiles, “IITian” or “IAS” are prized descriptors, almost personality traits. This glorification of educational badges is very much in line with Veblen’s idea that as society develops, “the pecuniary standard of living” extends to non-material forms – here, a prestigious education acts as a status good. One could argue that clearing a brutal exam in India is akin to a costly signal of ability and perseverance, and society rewards that signal with status, regardless of the material output involved.

The downside is a sort of national obsession with a few narrow definitions of success, leading to neglect of other skills and careers. Art, creativity, vocational excellence – these took a backseat for a long time because they weren’t seen as status-conferring. This is slowly changing with the rise of new industries and global influences valuing diverse talents, but the inertia of the old mindset is strong. When a country’s dinner conversations, parental pressures, and youth dreams are dominated by a handful of competitive exams, it is clear that status emulation is operating at full tilt, perhaps to the detriment of collective well-being.

Caste, Labour, and the Devaluation of Physical Work

In part 1, we spent a bit of time unpacking the class-caste dynamics of leisure, with the central focus being the twin Brahminical ideals of purity and abstention from physical labour. While the caste system is less rigid today, its imprint remains visible in how manual and skilled trades are regarded. The most stark example is manual scavenging—cleaning human excrement by hand—where approximately 95% of workers belong to Scheduled Castes (Dalits), a direct continuation of ancient caste-based labour assignments despite being legally prohibited. Beyond this extreme case, artisan and blue-collar professions like masonry, carpentry, and plumbing carry low social status regardless of their economic returns. Many consider these to be 'odd jobs' and not 'proper' jobs," even though skilled tradespeople often earn more than white-collar workers.

The upshot is the paradoxical situation that tradespeople are simultaneously in short supply and underpaid, while desk work can often be in high demand despite meagre wages. The macro-level effects create a paradoxical labor market: employers cannot find enough skilled technicians while millions of graduates remain unemployed. Many trades suffer a shortage of young entrants as children of traditional craftspeople seek escape to white-collar sectors. This mismatch is driven not just by economics but by status considerations.

Caste also influences the domestic setup of the leisure class itself. Many wealthy or middle-class households employ servants (maids, drivers, cooks), often from lower caste or migrant backgrounds. The presence of servants performing all household chores is a classic example of conspicuous consumption of service – their labour allows the family to engage in leisure or “higher” pursuits like charity and religiosity, and their very employment is a signal of refinement and standing. Veblen’s concept of vicarious leisure — the idea that the leisure class shows status by having others do the work for them — is on full display here. It’s notable that even families that aren’t extremely rich strive to hire some domestic help: in part because having servants has itself become a marker of being “upper” middle class, and likely also because it allows space for the womenfolk to also enjoy some measure of the leisure of their husbands and sons.

The class and caste dimensions overlap heavily: it’s almost taken for granted that the maid will be from a poorer, lower caste background. Some sociologists argue that the servant-master dynamic in urban India is a modern continuation of the patron-client caste relationships of the past, now monetised. And treating servants well (or poorly) also becomes a reflection of one’s values and status – there’s an old quasi-feudal pride some take in having had servants for generations, versus an emergent ethic among some urban liberals of treating domestic staff with more equality (still, they remain staff).

Even at the highest levels of wealth, caste-coded labour perceptions play out. Many industrialists in India come from traditional merchant castes or communities (Marwaris, Gujaratis, etc.), who historically did not do manual work but managed capital. When they set up factories, a certain distance often exists between them (as owners/management) and the shop-floor workers, who are usually from different social strata. Compare this to some countries where self-made industrialists took pride in knowing the factory floor – in India, that’s less common; management stays in air-conditioned offices, labour stays on the floor, and socialisation between the two is kept to a polite minimum.

Parent-child advice captures this mindset: the oft-repeat aphorism "padho likho, warna joote banane padege" translates roughly to “learn to read and write, or you'll have to make a living making shoes”. A useful skill is presented as a fate to avoid. Veblen would identify this as the "instinct of workmanship" being overridden by a "barbarian survival"—the association of labour with low status.

Urbanisation has led to some blurring of these distinctions, with higher caste individuals taking previously shunned jobs in the anonymity of concrete jungles. Initiatives like “Skill India” aim to elevate blue-collar work's status and seem to be working to reduce the stigma. Recent successes in mobile phone manufacturing and automobile assembly show manufacturing growth potential, but workers often require training from scratch as India's education system produces more MBAs than machinists.

Conclusion: Veblen in the Land of Contrasts

Had Veblen ever visited the subcontinent, one imagines him sitting on a balcony in South Delhi, notebook in hand, utterly vindicated yet endlessly fascinated. India offers not just examples of his theory—it provides the director's cut, with bass boosted to eleven.

The India of 2025 is a society where tech billionaires build skyscraper homes while millions live in informal settlements often within spitting distance; where IAS aspirants give up years of their formative years studying study 16 hours daily for a 0.1% chance at glory; where weddings become spectacles of consumption that make up a large portion of the national GDP and thus an inescapable part of the growth story of a GDP-obsessed establishment; and where families proudly announce “my daughter has an MBA but doesn't do any work”. Veblen wouldn't merely recognise these—he might have revised his manuscript to make it centred around the Brahmins of India instead of the emerging American aristocracy.

The application to India encompasses and elevates Veblen in so many ways. While his theory focused primarily on wealth, India operates a multi-currency status economy: caste capital, cultural capital, English-speaking capital, all circulate alongside money. Status here isn't a ladder but a complex chess game played in three dimensions. Yet there are hopeful countercurrents. Start-up founders are becoming the new heroes, making creation cooler than consumption. Women push back against the gilded cage of vicarious leisure. These shifts suggest status norms aren't written in stone but shaped by economic incentives and exposure to new ideas.

As India continues its dizzying ascent, it faces a crucial question: can it harness status competition toward more productive, equitable ends? Can the energy poured into cracking exams be redirected toward solving climate change? Can the desire for respect be satisfied through innovation rather than acquisition?

Thorstein Veblen's The Theory of The Leisure Class is more than just sociological observation—it's a moral philosophy disguised as social science, a critical mirror held up to society's vanities. His insights transcend their 19th-century origins to speak directly to our present moment. Despite the centuries between his world and ours, the resonance is startling. His lens helps us see patterns in daily life we might otherwise miss—from Instagram displays to educational anxieties to marriage markets.

The true value of Veblen's work lies not in perfect applicability but in its power to make us question what we take for granted and recognise the constructed nature of our collective desires. Ultimately, to imagine a world governed by different metrics of human worth. In that pursuit, each reader will find their own interpretation, their own application to the world they know and experience. Veblen offered one way of seeing.